In Part 1, I gave an overview of product diversification in an income portfolio. By way of illustration, I presented two extremes, where each portfolio had only one product, namely equity investments or an annuity (guaranteed income stream).

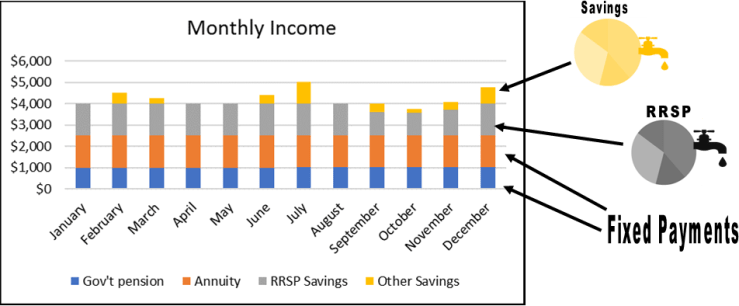

Here in Part 2, I show you what product diversification looks like (also known as “income layering”).

At the base is a fixed amount of income that may come from government pension payments such as CPP (Canada Pension Plan) and OAS (Old Age Security). These payments remain fairly level or increase slightly with inflation. An annuity can be from a company pension plan or through a purchase with an insurance company. These first two layers form the foundation of your income portfolio and are usually guaranteed for life.

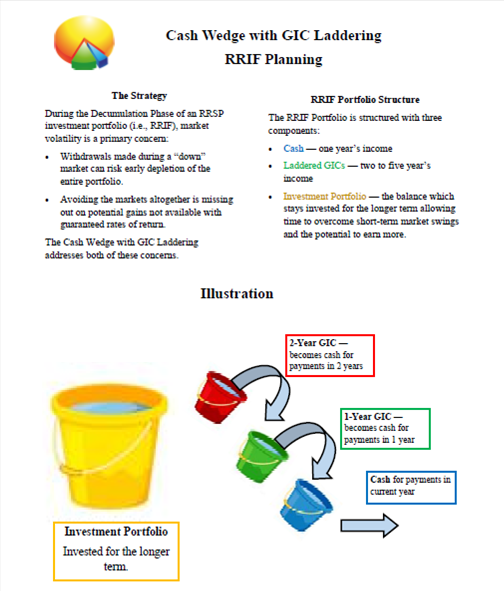

On top of these foundational layers are registered and non-registered savings. Some savings are invested for long-term growth and some are deposited in guaranteed options, such as GIC’s (Guaranteed Income Certificates) or daily savings accounts.

The above illustration shows that monthly income needs vary. Other Savings are available to draw upon when needed. As well, savings that are invested may undergo a market downturn during which time, it may be wise to decrease the flow of redemptions.

An income portfolio that has product diversification is better equipped to handle your varying financial needs throughout your retirement.

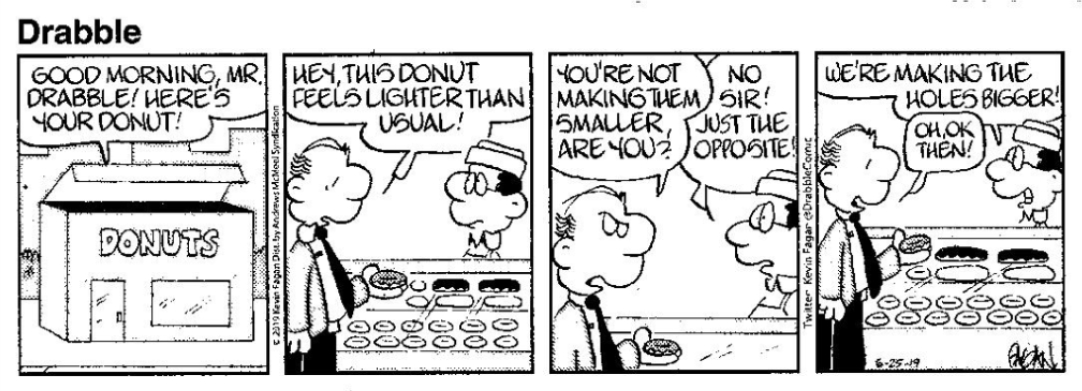

Some years ago, Cottonelle toilet tissue re-branded their product as Cashmere. But in doing so, the product and the packaging underwent an evolution of changes where the product shrank in size while the price remained about the same.

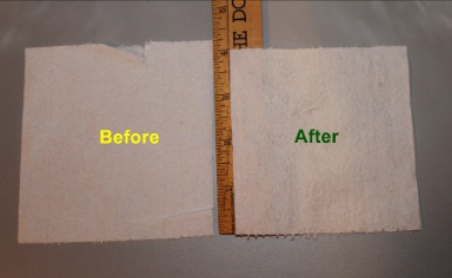

Some years ago, Cottonelle toilet tissue re-branded their product as Cashmere. But in doing so, the product and the packaging underwent an evolution of changes where the product shrank in size while the price remained about the same. And that’s not all. Even the size of an individual square has been reduced.

And that’s not all. Even the size of an individual square has been reduced.